Author: Prathik Desai, Source: TokenDispatch, Translated by: Shaw, Jinse Finance

In the late 1980s, Nathan Most was working at the American Stock Exchange. However, he was neither a banker nor a trader. He was a physicist who had worked in the logistics industry for many years, handling the transportation of metals and commodities. Financial instruments were not his starting point; practical systems were.

At that time, mutual funds were a popular way to gain broad market exposure. They provided investment diversification but had delays. You couldn't trade all day long. After placing an order, you had to wait until the market closed to know the transaction price (by the way, they still use this trading method today). This experience felt outdated, especially for those accustomed to real-time individual stock trading.

Nathan proposed a workaround: develop a product that tracks the S&P 500 index but trades like a single stock. Package the entire index into a new form and list it on the exchange. This proposal was met with skepticism. Mutual funds were not originally designed to be bought and sold like stocks. The relevant legal framework did not exist at the time, and the market seemed to lack demand in this area.

But he continued forward.

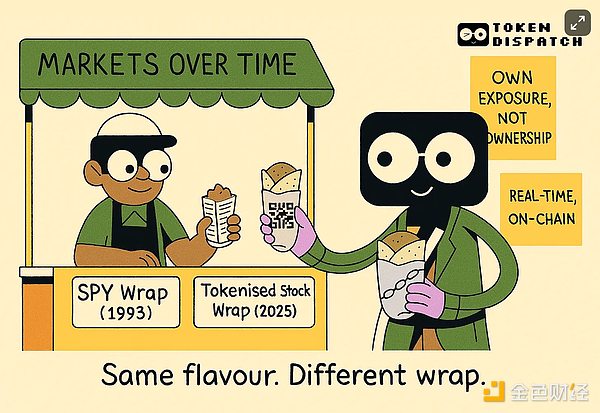

In 1993, the Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipts (SPDR) made its debut with the stock code SPY. It was essentially the first Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), a tool representing hundreds of assets. Initially viewed as a niche product, it gradually became one of the most actively traded securities globally. On many trading days, SPDR's trading volume even exceeded the stocks it tracked. SPY's synthetic structure achieved higher liquidity than its underlying assets.

In 1993, the Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipts (SPDR) made its debut with the stock code SPY. It was essentially the first Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), a tool representing hundreds of assets. Initially viewed as a niche product, it gradually became one of the most actively traded securities globally. On many trading days, SPDR's trading volume even exceeded the stocks it tracked. SPY's synthetic structure achieved higher liquidity than its underlying assets.

Today, this story seems significant again. Not because of a new fund launch, but because of what's happening on-chain.

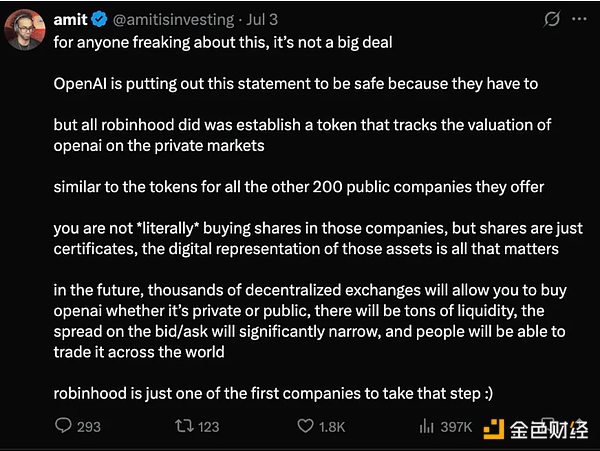

Investment platforms like Robinhood, Backed Finance, Dinari, and Republic are beginning to offer tokenized stocks - blockchain-based assets designed to reflect the prices of listed companies like Tesla and Nvidia, or even private companies like OpenAI.

These tokens are positioned to gain exposure, not ownership. They are promoted as a way to gain exposure, not ownership. They do not confer shareholder status or voting rights. You are not purchasing traditional equity. What you hold is a token related to equity.

This distinction is important, as controversy already exists around this point.

OpenAI and even Elon Musk have expressed concerns about the tokenized stocks offered by Robinhood.

Subsequently, Robinhood's CEO Tenev had to clarify that these tokens actually enable retail investors to access these private assets.

Subsequently, Robinhood's CEO Tenev had to clarify that these tokens actually enable retail investors to access these private assets.

Unlike traditional stocks issued by companies themselves, these stocks are created by third parties. Some claim to hold and custody actual stocks with 1:1 backing, while others are entirely synthetic. The experience feels familiar: prices fluctuate like stocks, the interface resembles a brokerage app, although the legal and financial substance behind them is often weaker.

Nevertheless, they still attract a specific type of investor. Especially those investors outside the United States who cannot directly invest in US stocks. If you live in Lagos, Manila, or Mumbai and want to invest in Nvidia, you typically need to open a foreign brokerage account, meet high minimum balance requirements, and go through lengthy settlement cycles. A token trading on-chain and tracking the stock's exchange performance eliminates friction in the trading process. Imagine: no wires, no forms, no thresholds, just a wallet and a market.

This access method feels novel, although its mechanism is similar to the old.

But there's a practical issue. Many such platforms - Robinhood, Kraken, and Dinari - do not operate in many emerging economies outside the US. For example, it's currently unclear whether Indian users can legally and practically purchase tokenized stocks through these channels.

If tokenized stocks are to truly expand market access globally, the obstacles will not just be technical, but also regulatory, geographical, and infrastructural.

How Derivatives Work

Futures contracts have long provided a way to trade expectations without touching the underlying asset. Options allow investors to express views on volatility, timing, or direction, typically without purchasing the stock itself. In each case, derivatives become another avenue for investing in the underlying asset.

Tokenized stocks emerge with a similar purpose. They do not claim to be superior to the stock market. They simply provide another entry point, especially for those who have long been excluded from public investment.

New derivative products typically follow an identifiable development trajectory.

Initially, the market is chaotic. Investors don't know how to price, traders are hesitant about risks, and regulators are reluctant. Then speculators rush in. They test boundaries, expand products, and profit from imbalances. Over time, if the product proves effective, it gets adopted by more mainstream participants. Eventually, it becomes infrastructure.

Index futures, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), and Bitcoin derivatives on CME and Binance started similarly. They were not initially tools for everyone. At first, they were playgrounds for speculation: faster, riskier, but more flexible.

Tokenized stocks might follow the same development path. Initially, retail investors will use them to gain exposure to hard-to-reach assets (like OpenAI or unlisted companies). Then, arbitrageurs will operate on price differences between tokens and underlying stocks. If trading volume remains stable and infrastructure matures, institutional trading departments might start using them, especially in jurisdictions where compliance frameworks gradually improve.

Early market trading activity might look noisy, with thin liquidity, wide spreads, and price gaps over weekends. But derivative markets often start this way. They are not perfect replicas. They are stress tests, the market's way of discovering demand before the asset itself adjusts.

This structure has interesting properties or flaws, depending on one's perspective.

Traditional stock markets have opening and closing times. Even most stock-based derivatives trade only during market hours. But tokenized stocks do not always follow this rhythm. If a US stock closes at $130 on Friday, and a significant event occurs on Saturday - like earnings leak or geopolitical event - tokens might start fluctuating, even though the stock itself is static.

This allows investors and traders to incorporate incoming news during stock market closure.

The time difference only becomes an issue if the trading volume of tokenized stocks significantly exceeds that of ordinary stocks.

Futures markets address such challenges through funding rates and margin adjustments. Exchange Traded Funds rely on authorized participants and arbitrage mechanisms to maintain price stability. At least so far, tokenized stocks lack these systems. Prices might deviate, liquidity might be insufficient. And the connection between tokens and their reference assets still depends on trust in the issuer.

However, this level of trust varies. When Robinhood issued tokens for OpenAI and SpaceX in the EU, both companies denied involvement. Neither coordinated nor had a formal partnership.

This doesn't mean tokenized stock issuance itself is problematic. But it's worth considering what exactly you're buying in these cases. Is it price exposure, or a synthetic derivative with unclear rights and recourse?

The underlying infrastructure of these products varies greatly. Some are issued according to European frameworks. Some rely on smart contracts and offshore custodians. A few platforms, such as Dinari, are trying more regulated approaches. Most are still probing the legal limits.

The underlying infrastructure of these products varies greatly. Some are issued according to European frameworks. Some rely on smart contracts and offshore custodians. A few platforms, such as Dinari, are trying more regulated approaches. Most are still probing the legal limits.

In the United States, the SEC has already indicated its stance on Token sales and digital assets, but the tokenized form of traditional stocks remains in a gray area. Platforms are also cautious. For example, Robinhood's issuance location is the EU, not its home market.

Nevertheless, demand is still evident.

Republic provides a synthetic channel for private companies like SpaceX. Backed Finance packages publicly traded stocks and issues them on Solana. These attempts are still in their early stages, but they continue, with a pattern aimed at reducing friction rather than financial issues. Tokenized stock issuance may not improve the economic conditions of ownership, as that is not their goal. They simply want to simplify the participation experience. Perhaps.

For retail investors, engagement is often the most important factor.

In this sense, tokenized stocks are not competing with stocks, but with the effort required to acquire stocks. If investors can obtain exposure to Nvidia with just a few clicks through an app that also holds its stablecoin, they may not care if the product is synthetic.

However, this preference is not new. SPY research shows that packaged products can become the primary market. The same applies to CFDs, futures, options, and other derivatives, which were initially tools for traders but ultimately served a broader audience.

These derivatives often even lead the underlying assets. In the process, they absorb market sentiment faster than the slower market below, reflecting fear or greed.

Tokenized stocks may follow a similar path.

The infrastructure is still in its early stages, with unbalanced liquidity and lack of regulatory transparency. But the potential driving force is obvious: creating something that reflects assets, is easier to access, and compelling enough to attract participation. If this representation can maintain its form, more funds will flow through it. Ultimately, it becomes not a shadow, but a signal.

Nathan Most's original intention was not to redefine the stock market. He saw inefficiencies and sought a smoother interface. Today's Token issuers are doing the same thing. This time, smart contracts, not fund structures, are doing the packaging.

Interestingly, it remains to be seen whether these new wrappers can win trust, especially during market turbulence.

They are not equity, nor regulated products. They are convenient tools. For many users, especially those far from traditional finance or in remote areas, this convenience may be enough.