By Andrej Antonijevic, Source: Bitcoin Treasury, Translated by Shaw Jinse Finance

summary

This article explores why the motto "Never sell your Bitcoin," while effective as a self-regulatory guideline for individual investors, can be counterproductive in a corporate setting. For a company holding Bitcoin as a treasury reserve, rigidity is not a virtue but a vulnerability. The core risk is that if shares must be issued at a significant discount, this could result in a permanent loss of value for shareholders.

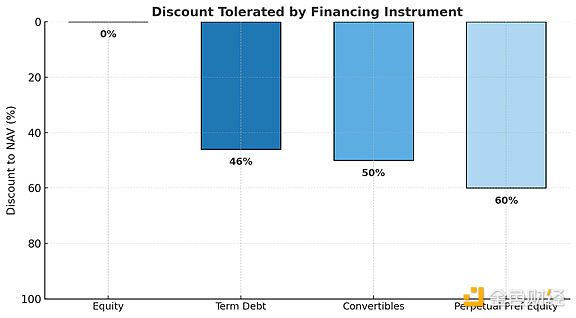

To quantify this risk, this article analyzes the break-even thresholds for four financing instruments: equity, term debt, convertible bonds, and perpetual preferred stock. Each instrument has a critical point beyond which rigidity erodes shareholder value. Pure equity strategies are the most vulnerable, unable to withstand a single haircut, while perpetual preferred stock is the most resilient. Convertible bonds and term debt fall somewhere in between.

The strategic point is that financing policy must be guided by flexibility. A balanced portfolio of instruments, coupled with a willingness to sell Bitcoin when thresholds are breached, is the only way to protect shareholder interests and prevent temporary market conditions from evolving into permanent value destruction.

Introduction

Among Bitcoin investors, the mantra "never sell your Bitcoin" has become almost an article of faith. For individual investors, the logic is simple: buy Bitcoin and hold it indefinitely to avoid missing out on long-term compounding opportunities by trading. With no interest payments, no refinancing plans, and no need to contend with stock market fluctuations, individual investors can easily follow this rule.

Corporations are different. A Bitcoin Treasury Reserve company is designed to create value and meet specific financial obligations. Depending on the financing mix, these obligations might include coupon payments, refinancing schedules, liquidity buffers, issuance discipline, or dividend distributions. Corporate finances are not static: financial instruments mature, coupons must be paid, and market conditions change.

For a company, a "never sell" stance can lead to rigidity, and rigidity breeds vulnerability. A blanket refusal to sell Bitcoin might sound like a good thing, but in reality, it creates a single point of failure. The risk is that the company could find itself having to issue shares at a significant discount, resulting in a permanent loss of value for shareholders.

The correct way to assess this risk is to analyze the instruments used on the balance sheet. Each instrument has different costs, flexibility, and pressure points. This article examines four core financing instruments: equity, convertible bonds, term debt, and perpetual preferred stock, to reveal the tipping point where rigidity becomes destructive.

Why Rigidity is a Risk

“Never sell Bitcoin” is a strict restriction. Strict restrictions transform ordinary market fluctuations such as stock premiums and discounts, coupon obligations, refinancing windows, and changing capital costs into corporate vulnerabilities.

A simple example comes from its equity issuance policy. Strategy (formerly MicroStrategy) recently stated that it would not issue shares to purchase Bitcoin at a price below 2.5 times book value (a 150% premium). The company later retracted this statement, clarifying that it would retain the flexibility to issue shares below this threshold if circumstances warrant. This is not an inconsistency, but a pragmatic adjustment in capital allocation strategy. Premiums and liquidity can disappear, and the cost of capital can be repriced within a day. Pre-committing to a fixed rule, whether it's an issuance threshold or a "never sell Bitcoin" policy, gives the market something it should never have: a predictable and unchanging counterparty.

Bitcoin itself was designed to avoid a single point of failure. A rigid "never sell Bitcoin" policy creates precisely that situation. The right approach is to maintain flexibility and define the necessary conditions for selling Bitcoin based on the unique circumstances of each instrument, as each instrument has its own break-even point, beyond which shareholder value is at risk.

Perpetual preferred stock

Perpetual preferred stock is a stock-like instrument with a fixed coupon rate and no maturity date, making it perpetual (perpetual financing capital). They are less risky than term debt because they have no refinancing risk and no repayment events that could cause a liquidity event.

However, such bonds require interest payments. If operating revenues are insufficient to cover the interest payments (a common scenario for Bitcoin Reserve companies whose sole objective is to increase their Bitcoin holdings), then these payments require issuing equity. This becomes more expensive when the stock trades at a discount.

In this case, the effective cost of capital (K) to fund the perpetual preferred stock by issuing equity can be expressed as:

K = C / (1-D)

Where C is the coupon rate and D is the discount to NAV. As long as the expected return on Bitcoin (R) is higher than the actual cost of capital implied by the coupon rate and the discount to NAV, then paying the coupon rate on the perpetual preferred stock with outstanding shares remains economically viable:

R>C/(1-D)

The above framework provides a clear approach to determining how deep a discount can be tolerated before the instrument begins to erode shareholder value.

For example, assuming an 8% coupon rate and an expected 20% compound annual growth rate for Bitcoin, the breakeven discount (D*) is:

D* = 1 − (C/R) = 1 – (0.08/0.20) = 60%

This means that the company's stock could trade at a discount of up to 60% to its net asset value before the coupon on the perpetual preferred stock exceeds the expected return on Bitcoin. This tolerable discount would narrow if Bitcoin's expected compound annual growth rate was lower, and widen if its expected compound annual growth rate was higher.

The framework is universal: the higher the expected return on Bitcoin, the larger the discount that can be tolerated, while the higher the coupon, the smaller the discount that can be tolerated before shareholder value begins to be eroded.

With permanent capital, management can usually withstand significant discounts. But once the break-even point is exceeded, refusing to sell Bitcoin can trap the company in a vicious cycle of destroying shareholder value. From that point on, the rationale is to sell Bitcoin, either to repurchase shares and restore parity with net asset value, to repurchase some of the outstanding preferred stock, or to pay coupons if the discount is deemed temporary.

term debt

Term debt is a traditional loan: interest must be paid during the life of the loan, and the principal must be repaid at maturity. For Bitcoin Reserve, a typical structure might be five-year debt with a 7% coupon rate.

The key question is how deep a discount to net asset value (NAV) can be tolerated before repaying this debt (including coupon payments and principal repayments) through equity issuance becomes disruptive. The break-even discount is:

D* = 1 − (1 + C xt)/(1 + R)^ t

Where C is the coupon, t is the term, and R is the actual compound annual growth rate of Bitcoin during the same period.

For example, consider a five-year bond with a 7% interest rate, the proceeds of which are used to purchase $100,000 worth of Bitcoin. Over the life of the loan, the total coupon payment is $35,000, and the $100,000 principal must be repaid, resulting in a total debt of $135,000. If Bitcoin's annual interest rate is 20%, then after five years, the value of the Bitcoin will be $248,832. Substituting these numbers into the formula yields:

D* = 1 − (1.35)/(1.20)^5 = 45.7%

This means the shares could trade at up to a 46% discount to net asset value and still break even. Beyond that level, the actual cost of debt service would exceed the gains from Bitcoin, and shareholder value would be destroyed.

The framework is universal: the higher Bitcoin's return, the greater the discount it can tolerate; the higher the coupon, the smaller the discount it can tolerate; and longer maturities increase discount tolerance because Bitcoin's compounding effect grows faster than the linear accumulation rate of coupons.

The primary risk is being unable to refinance at maturity, forcing repayment. If this must be accomplished by issuing shares at a discount, financial harm will only occur if the discount exceeds the break-even point. In this case, the right approach is to retain the option to sell the Bitcoin, either to pay interest or repay the principal, as refusing to do so could transform a temporary market condition into a permanent loss for shareholders.

Convertible bonds

Convertible bonds fall somewhere between fixed-term debt and equity. They are issued as bonds with a fixed coupon rate and maturity (typically five years), but investors have the option to convert them into equity at a pre-agreed premium (usually around 40% of the issue price). Convertible bonds typically have low coupon rates (e.g., 0.4% per annum), reflecting the potential for equity upside. Their economic returns depend on performance over the life of the instrument.

If the share price increases by less than the conversion premium, the conversion option is not exercised, and the instrument behaves like a term debt. Coupon payments must be made, and principal must be repaid at maturity. Therefore, the same framework as term debt applies. Assuming a 20% annual compounded interest rate for Bitcoin, a five-year term, and a 0.4% coupon, the breakeven discount is approximately 59%. In other words, because the coupon is so low, this structure can withstand a higher discount than term debt with a higher coupon before shareholder value is eroded.

If the share price rises by more than the conversion premium, bondholders will convert the bonds into shares at the agreed-upon premium. In this scenario, the company effectively issues new shares at a 40% premium to the original share price. Even if the shares trade below net asset value at the time of conversion, the base price remains the original issue price plus the premium. This effectively creates a result similar to a stock issue at a premium, creating a value-added effect.

For convertible bonds, the return on Bitcoin is crucial because it determines whether conversion occurs. If Bitcoin's appreciation offsets the conversion premium, the effective issue price resets to near parity. If not, the instrument behaves like a term debt and inherits the same sensitivities.

Convertible bonds also provide strategic flexibility when the stock is trading at a significant discount. For example, if the stock is trading at a 40% discount to net asset value (NAV), issuing ordinary shares would be disruptive. However, issuing convertible bonds with a 40% conversion premium effectively allows the conversion price to be set at par with NAV. If Bitcoin appreciates and triggers conversion, the company will issue shares at par rather than at a significant discount. This allows the convertible bonds to "take the heat" when financing is needed. However, there is a limit to the discount. If the stock is trading at a discount greater than the conversion premium—for example, more than 40% in this example—conversion will not occur, and the bonds will revert to regular bonds, carrying the aforementioned risks.

Thus, in summary, a five-year convertible bond with these terms can be considered to withstand a discount of approximately 50% to net asset value before shareholder value is impaired.

The framework is universal: the lower the coupon rate, the greater the tolerance for discounts, and the higher the conversion premium, the more flexibility a company has to issue equity without destroying value. However, if the share price consistently fails to break through the premium, the instrument will eventually degenerate into a regular bond, with all the associated limitations.

Equity

Equity represents a share of ownership in a company. Its economic benefits depend on whether the stock trades at a premium or discount to its net asset value.

At a premium, issuing shares to purchase Bitcoin increases the value of each Bitcoin. At a discount, issuing shares can damage shareholder value and potentially cause permanent capital loss. At par, issuing shares is neutral. At a discount, stabilizing the share price is through share buybacks, funded by selling Bitcoin, thereby narrowing the gap.

A company that pre-committed never to sell Bitcoin loses this stabilizer, increasing inflexibility and risk. If no action is taken, a temporary discount could persist: the company cannot issue shares at these levels, and the "machine" stops accumulating Bitcoin. Therefore, selling Bitcoin to buy back discounted shares is not a deviation from the company's mission, but rather a way to protect shareholder value, maintain Bitcoin reserves, and, more importantly, increase the value of each Bitcoin share.

Taken alone, if shares are the only available instrument, the conclusion is simple: below parity, Bitcoin should be sold to buy back shares. The framework for this particular case is universal: the breakeven discount on equity issuance is equal to 0%.

In practice, however, rather than selling Bitcoin, companies might consider issuing other financial instruments, such as perpetual preferred stock, convertible bonds, or term debt, to raise funds for coupon or principal payments. These instruments can maintain their value even at deeper discounts. But access to funding isn't always guaranteed. Credit markets see the same signals as equity markets. When stocks trade at a discount, lenders may demand higher coupons, stricter covenants, or simply refuse to provide funding. The market understands that a reluctance to sell Bitcoin increases the rigidity of funding and may be hesitant to provide financing to balance sheets that are at risk of permanent capital losses.

Therefore, the principle remains the same: issuing shares below net asset value destroys shareholder value, and the mechanism for stabilizing the stock price is to sell Bitcoin to buy back shares. If executed properly, such buybacks are not only defensive but also increase the value of each Bitcoin.

Strategic Points

The chart below shows the maximum discount to net asset value that different financing instruments can sustain before shareholder value begins to be eroded.

Pure equity strategies are the most fragile: once shares trade at a discount, the Bitcoin accumulation mechanism ceases, and issuing shares below net asset value will destroy shareholder value. On the other hand, perpetual preferred stock is the most resilient, with convertible bonds and fixed-term bonds falling somewhere in between.

This framework does not consider tax considerations. In practice, selling Bitcoin may generate a taxable gain, reducing the net proceeds available for repurchases. This means that in jurisdictions with higher capital gains taxes, companies can afford to take a larger discount before selling to the market. Therefore, the thresholds proposed here should be viewed as pre-tax reference points.

Opening up access to debt-like instruments could enhance resilience by enabling Bitcoin Reserve to weather market volatility within its respective thresholds while preserving shareholder value.

The key is that a combination of equity and debt-like financing creates the most robust structure. The general framework outlined above provides guidance: the lower the coupon rate on any debt, the better; and the longer the maturity, the better, with perpetual instruments offering the greatest resilience.

It's clear that financing policies must be guided by flexibility, not rigidity. "Never sell Bitcoin" is an unnecessary restriction that will cause harm once the threshold is breached. Maintaining flexibility in financing and being willing to sell Bitcoin when necessary is crucial to protecting shareholder value.