Today, I want to write an article summarizing the Automatic Deleveraging (ADL) mechanism in the crypto market. The reason for writing this article is that I have recently received many messages about ADL and issues with this mechanism in many exchanges.

Additionally, ADL is purely related to the crypto market - this is not something you would see in traditional financial markets (if I'm wrong, please correct me). Today, my goal is to briefly explain what ADL is, what problems it has, and why Bybit (possibly not just this exchange) has done many suspicious things with the ADL mechanism, and not everything is clear.

Let me first explain what ADL is.

Actually, there is currently no clear, comprehensive whitepaper explaining how ADL works, lacking clear examples, possible solutions, and plans for the mechanism's development.

A friend of mine recently provided me with ADL data for MANEKI on the Bybit futures platform. I will slightly modify some numbers (without changing the range and percentage variations) to protect his anonymity.

Automatic deleveraging is a mechanism that closes the most profitable positions (positions opened with maximum leverage), occurring when the exchange cannot continue liquidating other customers' positions without incurring losses.

Let me explain more clearly, in case the previous explanation was not clear enough. Suppose there is a massive market fluctuation, with prices dropping significantly, causing many customers' accounts to be forcibly closed.

Assume we are at a specific moment when only one customer is being forcibly liquidated. Suppose the customer's position value in $MANEKI is $50,000. For such a position, to avoid forced liquidation, your account needs to maintain $2,500 (because the maintenance margin ratio for this position is 5%).

If your "account value" is below $2,500, your position will be forcibly closed - that is, the maintenance margin is the cash you need to keep in your account to hold an open position.

Suppose the market continues to fall, and you lose a lot of money on your open position, causing your account to drop below $2,500 - at this point, the automatic liquidation process will be triggered.

Let's assume some terms:

- Liquidation Price → The price of $MANEKI when your account is forcibly closed

- Bankruptcy Price → The price of $MANEKI when your account value becomes 0 (if you are long, this price should be strictly lower than the liquidation price, because at the liquidation price, your account should still have approximately the maintenance margin balance)

- Execution Price → The market order price associated with account liquidation.

Your account is closed through a market order (sell), and the exchange gets the weighted average transaction price for that order.

Next is a very important point - if the execution price (EP) (assuming you are long) is higher than the bankruptcy price (BP), theoretically your account value should not be 0 (because the account value is only 0 when liquidation occurs at BP). However - you will not receive this additional funds - these funds are taken by the exchange.

If the exchange can execute the order at a better price than BP, it will collect this surplus (and - according to the documentation - may invest it in the insurance fund).

We'll return to this issue later, but now let's focus on a more complex situation:

Suppose market volatility prevents the exchange from executing the order at a price better than BP. In this case, the account's "account value" will be below 0, and the exchange will use the insurance fund to cover the losses.

The insurance fund is a "reserve pool that the system can use to protect traders from excessive losses in derivatives trading."

Therefore, any forced liquidation orders below the bankruptcy price will cause additional losses, and the insurance fund will be used to cover these losses - this fund is usually composed of the exchange's funds or additional profits collected from liquidations.

This is the ADL mechanism we ultimately want to discuss - if the insurance fund cannot cover the losses (because there's no money in it), the exchange will activate the automatic deleveraging mechanism to make up for this gap.

I want to define it as accurately and clearly as possible: ADL allows the exchange to offset liquidation losses with profitable customers' positions.

So, if a customer's position is forcibly closed and the insurance fund cannot absorb the losses, the exchange will find a profitable customer and forcibly close part of this profitable position to compensate for the losses.

Suppose the exchange needs to liquidate a position worth $30,000: the insurance fund cannot cover the losses, and the exchange ranks customers based on the formula: Profit × Leverage. Assuming the top-ranked customer holds a position worth $100,000, the exchange automatically closes $30,000 of this profitable position.

No liquidation order will be sent to the market - this will not affect the order book, and the entire impact will be silently absorbed by profitable customers, with no warning.

It sounds a bit crazy - but this is basically how it works.

You could say this is a "over-profit protection" mechanism established by the exchange.

I guess you should understand this mechanism now (I really hope so - I always try to explain slightly complex things in a simple way). Now we can start discussing some questions and problems I have about this mechanism.

What are the strange aspects of ADL?

First, the problem is that we know very little about the ADL mechanism. For example, we don't know when the exchange decides it cannot properly execute liquidation orders and must resort to the ADL mechanism. This could happen at any time, with no explanation.

For example, Carol Alexander wrote an excellent article about the insurance fund and some volatility events.

There's a very strange point: on May 19, 2021 (all serious crypto traders in 2021 should know this date - if you don't, I recommend making a cup of tea and spending at least an hour looking at the data from that day), there was a massive sell-off and forced liquidation event.

But when we examined Binance Futures' insurance fund data, we found that the insurance fund actually grew that day - it was not depleted!

I know it should have been emptied because I was personally ADLed on many contracts - clearly, something was wrong with the mechanism. I strongly recommend you read this article.

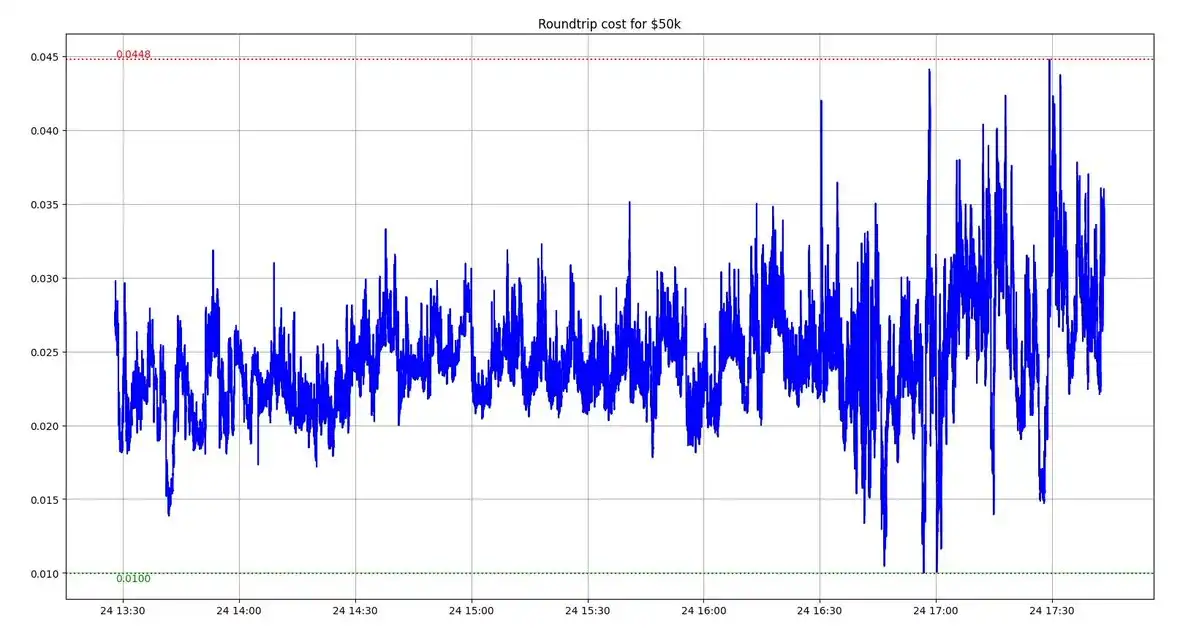

Let me return to the decision problem between ADL and market sell orders. Regarding market sell orders and potential slippage: During the massive ADL event for $MANEKI (which I assume was quite significant, as I know many people were affected in the past few days), the reversal cost for a $50,000 order (i.e., the cost of simultaneously buying and selling market orders) did not significantly increase compared to before the large-scale liquidation event.

Recall: For a $50,000 order, the maintenance margin ratio is 5% - even during massive volatility, the reversal cost (not just the one-sided cost) is lower than this.

For larger positions (and thus potentially greater market impact), you will anyway have a higher maintenance margin ratio.

Next, a very crazy point is the difference between the mark price (assuming this is the price at a certain moment in the market) and the ADL price.

In my friend's case, his ADL price was around 0.0033, but the mark price at the time of ADL (i.e., the actual market price) was 0.002595 - the difference is extremely large.

Even crazier - the price of 0.0033 had already disappeared from the market for over 30 minutes when the ADL occurred.

Why didn't the exchange immediately execute ADL after liquidating other customers (assuming 0.0033 is the liquidation price)? Why did they decide to wait 30 minutes before executing?

A previously profitable trade became a 30% loss when the ADL occurred. Because we have no information about historical ADL or its mechanism, the exchange can essentially operate arbitrarily.

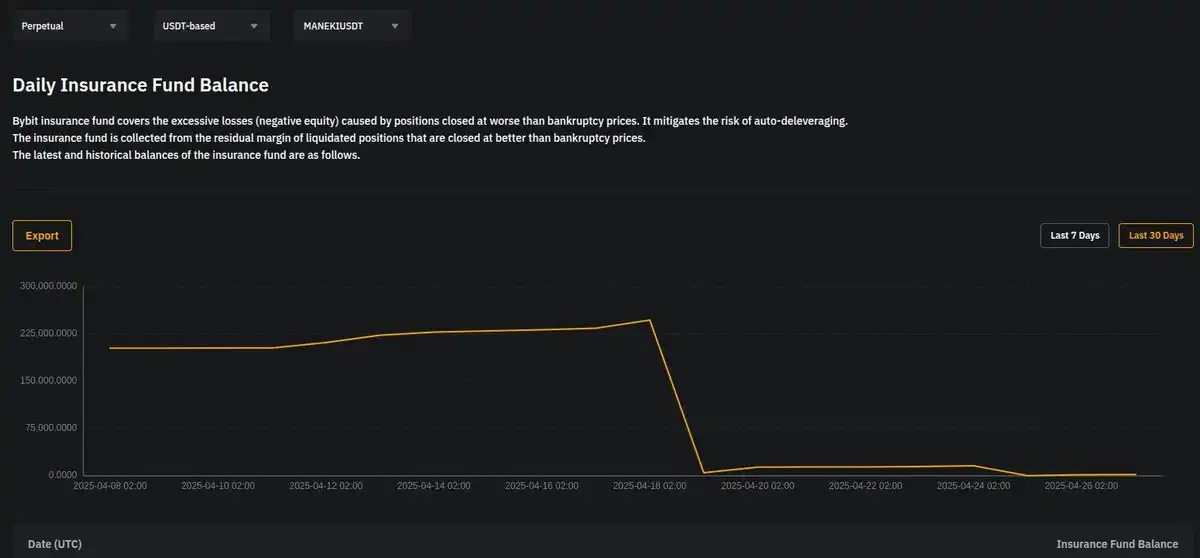

I tried to verify with others whether there were similar price differences and crazy ADL situations - yes, I found confirmed cases. But the story isn't over. Before these strange events, the insurance fund had been empty for several days.

I mentioned the story of April 24th before, but you can clearly see that the insurance fund had been almost depleted since April 19th - and Bybit did nothing.

They could have done many things: adjust the maintenance margin, add funds to the insurance fund, introduce better protection measures for customers.

But they did nothing.

A massive sell-off (over 40%) occurred the day before Bybit announced delisting $MANEKI.

For the curious, I have provided the crazy, absurd, manipulated chart of $MANEKI a few days before the sell-off. But from Bybit's perspective, no one paid any attention to this.

I hope that through this crazy $MANEKI example, I can somewhat explain what ADL is.

I believe that understanding the liquidation process, ADL mechanism, and all content related to perpetual contracts and margins is crucial to fully comprehending the cryptocurrency market.