Author: Yuqian Lim

Compiled by: TechFlow

False headlines and stock market volatility

Earlier this week, the stock market surged on a false headline claiming that President Trump might suspend new tariffs for 90 days. However, just hours later, the stock market quickly fell again when it was discovered that the news was not true. The fake news originated from a Twitter account named Walter Bloomberg (which is not affiliated with Bloomberg and has shown signs of being run by an individual on several occasions), which seemed to have copied a headline from somewhere (or could have been intended to manipulate the market, who knows).

The market’s reaction is important because it reveals how desperate the market is for an end to tariffs. Investors are so eager to believe any shred of good news that even false information can spark a rally.

However, there has been no real good news from the administration so far. On Tuesday, the market was hopeful and generally up, but then it let out a sigh of resignation and quickly fell after realizing that tariffs were coming.

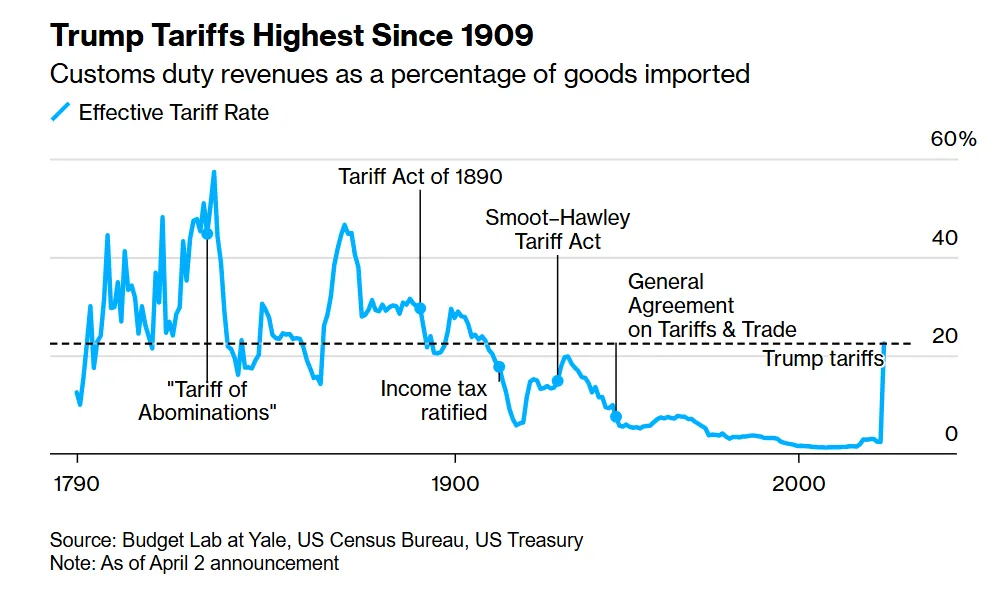

And those tariffs did come—the largest tariff increase in U.S. history took effect at 12:01 a.m. on April 9. In fact, the tariffs were so punitive that they actually began to reduce revenue, as Ernie Tedeschi has written.

There are many questions here: Why do fantasies of 1950s factory America obscure the realities of modern labor and technology? Are bond markets failing? What will Congress do? How will China respond? What should we do next?

What happened to the bond market?

First, let’s look at the bond market.

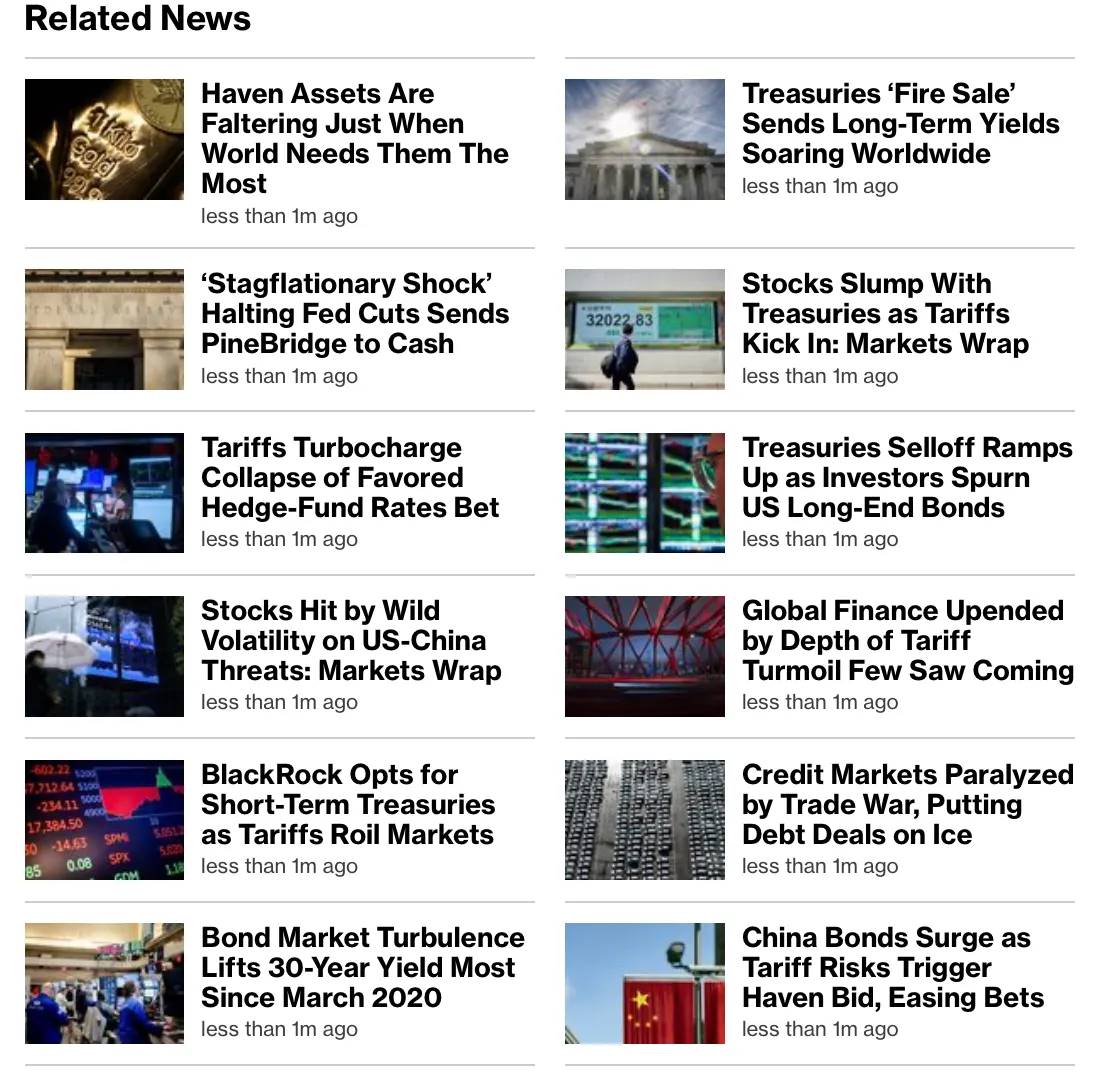

The bond market is selling off, and this is happening in the middle of a stock market crash. The U.S. is a risk to the world right now, and it has temporarily thrown markets into disarray. Here are some of the headlines that give us a sense of how volatile the situation is right now.

The stock market is falling because tariffs will impact the real economy. Normally, when the stock market falls, we see a flight to safety - when the market panics, people think, "Well, U.S. Treasuries look safe. The U.S. is a stable country, I'll buy some! Nothing can go wrong!" So people buy Treasuries, pushing up bond prices and lowering yields.

But now, that’s not the case. Yields are rising, which means people are selling bonds, which could herald a new era. Why is this happening? There are several reasons:

China is selling: The bond sell-off could be because China or other foreign governments are selling U.S. Treasuries out of retaliation or fear.

Forced selling: As Matt Levine explains, market deleveraging can trigger the unwinding of underlying trades, leading to forced selling and even the blowup of hedge funds.

No more safe haven status: Maybe people are starting to worry that the “safe haven” is no longer safe. If other countries think the U.S. government might withdraw the Fed’s swap lines for political gain, or suspect the White House might keep levying tariffs until the economy collapses — they might decide, “Forget it, I won’t buy Treasuries, thanks.”

Market Sentiment: This depends a lot on people’s perception. Market sentiment does matter as it is a leading indicator of actual data and market positioning.

This leads to a tricky question - when and how will this stop? Right now, everything is falling - the dollar, oil, bond prices, stocks, and credit spreads are soaring. This is also bad news for the housing market. Everything is going in the wrong direction. So, who can do something?

Could the Fed or Congress step in?

Maybe the Fed will step in? But with inflationary pressures so high (due to tariffs), the Fed can't easily cut rates and instead chooses to maintain the status quo, as San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly has said. Of course, the Fed could also do quantitative easing (QE) and buy some bonds, but this would further increase inflationary pressures.

Congress could step in, too. That’s their job . Remember, all of this is being done in the name of emergency action. They can call it quits at any time. As The Washington Post writes, “Seven Republican senators are backing a bipartisan bill that would roll back the new tariffs after 60 days unless Congress votes to approve them.” But they’d need at least two-thirds of the senators (and 20 Republicans) to override a possible Trump veto. They don’t seem to want to do that.

As a result, some senators—particularly from states dominated by manufacturing—might push for more targeted trade deals to mitigate the impact of tariffs on local businesses. Others, especially in states where agriculture is a major employer, might lobby for exemptions or partial tariff relief in response to retaliation from other countries on U.S. agricultural exports. If the situation worsens, a bailout package for farmers could be in the works, as was the case with previous tariffs (although that would offset any revenue from the tariffs).

At the state level , governors may negotiate local business partnerships or foreign direct investment agreements. For example, a state could offer tax incentives or streamlined approval processes to attract companies to build factories locally, effectively creating small trade or investment zones. This could create tensions between state governments and White House policies, but state governments need to protect local jobs.

The real problem is the federal government: ideally, the government would remove the tariffs, but when policy becomes showmanship, that doesn’t happen. As of the morning of April 9, Trump refused to get back to anyone in the negotiations (despite their “fawning over him”), and now he’s even talking about tariffs on pharmaceuticals, Politico reported.

The core of the yield problem is that the government wants to keep it down so it can refinance its debt at a lower rate, pay less interest, and walk away. But now, not only is the possibility of a recession looming, yields are not falling—it’s a perfect stagflation combination: high inflation, low economic growth, and high unemployment.

Shifting World Order:

If you’ve read my previous posts, you’ll know that I’ve been critical of these tariffs (even before the election, when I first interviewed Erica York of the Tax Foundation). The current administration’s basic demand is that other countries either pay the new trade fees or they can’t trade with us anymore.

So what does the US really mean to the rest of the world? Many people think the US is subsidizing the rest of the world, but in fact the opposite is true, as Ben Hunt writes.

The United States is the primary beneficiary of a global system based on stability and trust. In fact, the rest of the world has been subsidizing the American way of life. This stable system, once known as Pax Americana, has provided other countries with security, open trade routes, a stable dollar, etc. for nearly 80 years in exchange for allowing the United States to exert extensive influence on global rules and institutions. As a result, the United States enjoys unique privileges, such as lower borrowing costs and persistent trade deficits (which are not actually a bad thing), while other countries' demand for dollars and U.S. Treasuries actually subsidizes the U.S. standard of living.

But now the US has turned around and demanded an additional fee that doesn’t fit any reasonable calculation (in fact, the math used is wrong, as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) points out). So countries are starting to ask: “If the US is going to haggle over every freighter and submarine, why don’t we just make our own trade deals and avoid all this trouble?” As a result, we’re pushing them away and undermining our own advantage: trust.

All of this is changing, and perhaps the status of reserve currencies will change with it. In the past, we had only one big question: "Will China replace the dollar?" But this question may be too simplistic. We may see the formation of a series of "currency clubs", as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has previously explored, such as small groups or bilateral agreements, some based on digital clearing systems, some partially pegged, which gradually reduce dependence on the United States.

Rather than a single competing currency replacing the dollar, we may see a patchwork of currencies that collectively reduce the influence of the U.S. The end result is the same: less automatic demand for U.S. Treasuries, more fragmented markets, and less reflexive “safe havens.”

How will China respond?

Many believe that the ultimate goal of this game is to weaken China. US Treasury Secretary Bessent said they may delist Chinese companies from US stock exchanges because "all options are on the table". At the same time, China has fought back and imposed a 50% tariff on US imports. This marks that we have officially entered a trade war.

The yuan is falling, and China is trying to make its exports more competitive by devaluing its currency (a strategy that is extremely complex and has many secondary effects), while also possibly preparing for a capital war with the U.S. China is a difficult adversary for several reasons:

China is not nearly as dependent on the US as it once was: China has diversified its export markets, sending more goods to Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. The US is no longer as important a share of China's total exports. Some might argue that "the US is bankrupting all the countries with these tariffs so they can't afford Chinese goods." That sounds like rearranging the chessboard in another dimension, but there may be some truth to it.

China can bear more pain than the US: This is a complex argument, but the American public is angry about inflation in the final year of the Biden administration. If tariffs push up inflation again (which is likely to happen, as Trump’s first-term tariffs already made imports more expensive), this could seriously hurt Trump’s poll numbers (maybe?), although the administration seems to think it will strengthen its position with Main Street. (Frankly, “Main Street” and “Wall Street” are pretty much the same thing these days.)

China has excellent factories: China is not afraid of automation like the U.S. Their factories are already highly automated, even fully automated.

This does not include many high-end electronics, batteries, and almost all goods on Amazon that still rely on China's supply chain. If the United States really wants to isolate China, then commodity prices will rise sharply. And American consumers are used to cheap goods, and it is conceivable what kind of reaction this price increase will cause.

We often think of big trade blocs as being driven by governments. But remember, tariffs are paid by companies that export goods to the US, not by countries. Increasingly, multinationals like Apple and Samsung may need to engage in some form of “corporate diplomacy” to ensure supply chain continuity. They may need to establish new shipping routes and manufacturing bases outside the US, forming a quasi-private global network that could ultimately be more important than the official institutions led by Washington.

However, this is all, of course, very complicated. As Scott Galloway has noted, Trump has done enormous damage to “Brand America,” and that is certainly bad news for American companies.

Myths and Realities of Reshoring Manufacturing

Part of the government’s official justification is that “we just need to make everything locally”. This reflects their obsession with reviving traditional manufacturing. However, the reality is more complicated, and the following points are worth noting:

Manufacturing is already growing: As Joe Weisenthal points out, U.S. manufacturing has actually boomed over the past four years, driven by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS Act, and that growth has not relied on broad tariffs.

Nostalgia for a bygone era: The administration has repeatedly mentioned scenes like workers assembling screws in phones in the 1950s, and even Trump prefers to compare the United States to the "golden age" of 1870 to 1913 (when there was no income tax). These nostalgic images do have a certain appeal politically: the image of a steel mill or assembly workshop symbolizes the strength of the US economy, especially after the two world wars, when the United States was the only country with production capabilities. But that era is gone forever.

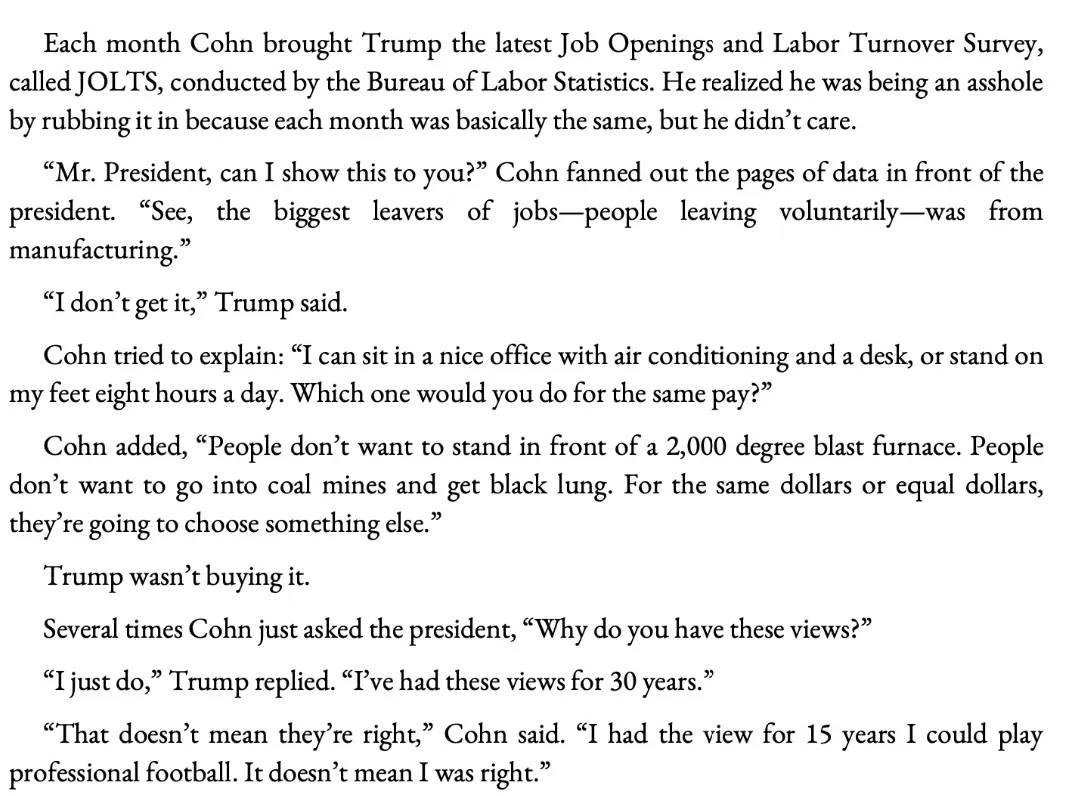

This won’t solve our social problems: Many people try to speak for ordinary people, like some commentators. They think that returning to manufacturing is the key to solving the problem. However, the fact is that people leave manufacturing in large numbers when given the opportunity. This is not to say that manufacturing is not important (it is!), but the problem is much more complicated than it seems.

Anecdote: Jordan Schneider shared this quote from Gary Cohn about Trump when looking back at Trump's first term. People are leaving manufacturing, in part because it's hard and monotonous work. While we've made great strides in improving the working environment with machines, if people have a choice, they'll definitely prefer to do a job that doesn't involve driving tiny screws into a phone. People are more likely to work in aerospace or go into semiconductor factories (and there would be more opportunities if the CHIPS Act hadn't been repealed!).

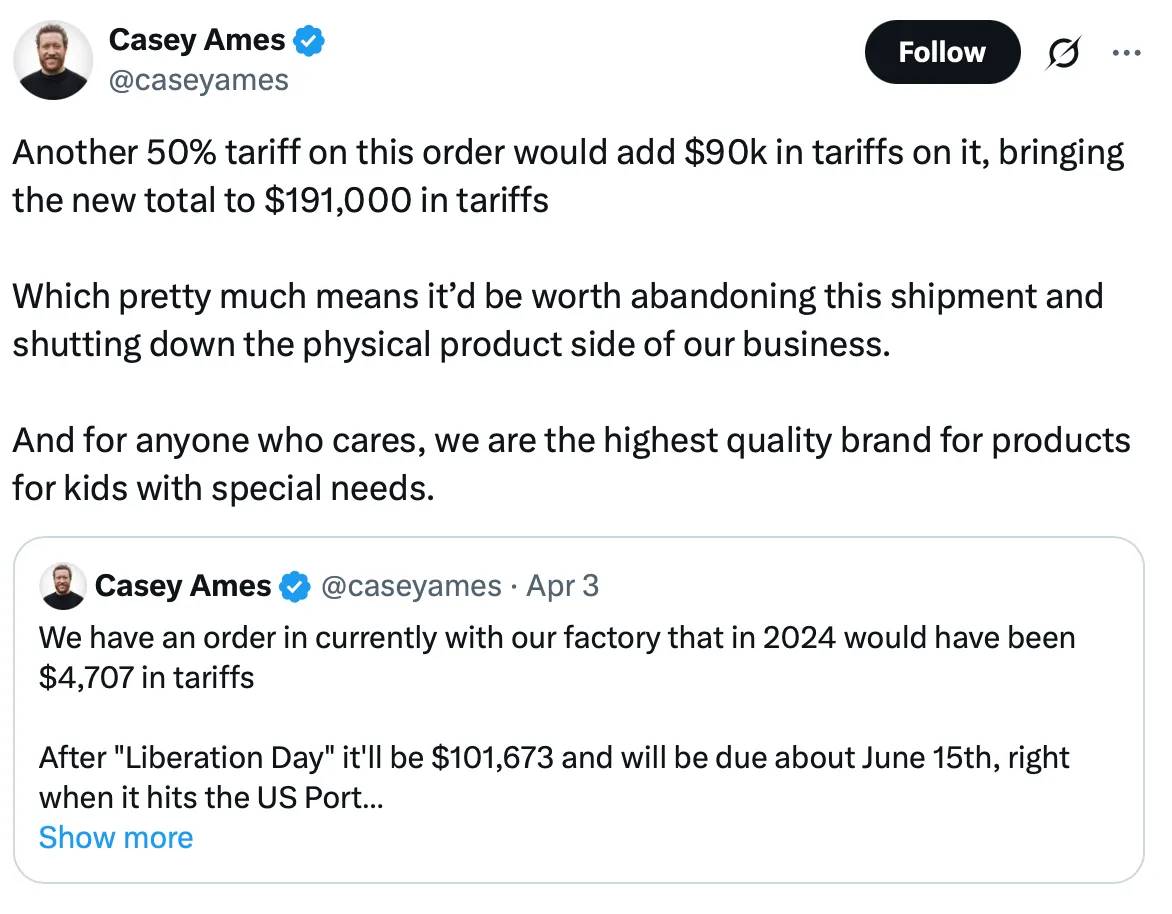

It’s not just Wall Street that’s worried: David Bahnsen compiled a list of the impacts of tariffs on Main Street that shows a lot of worry and fear. To think that reshoring manufacturing will solve the “loneliness crisis” or other social problems is to completely misunderstand the real root problems in our world. The problems are smartphone adoption and the housing crisis. When Trump took office, the United States was already at full employment.

This won’t bring back many jobs: Modern factories require far fewer workers to operate, and the government acknowledges this. Today’s manufacturing jobs often require higher skills, such as programming CNC machines, which require workforce training, faster approval processes, and other factors beyond taxes. As Alex Tabarrok has detailed, tax incentives alone can’t solve these problems.

This leads to a lose-lose-lose-lose situation.

If we promote onshoring but rely on robots to do the work, we will neither get cheap foreign labor nor create a large number of local jobs.

So you might see a reduction in foreign supply chains (which means less U.S. soft power) but also no new wave of U.S. jobs.

Manufacturers are actually pulling back on spending amid uncertainty, a trend already seen at Haas Automation, a company that makes CNC machine tools, and Microsoft’s decision not to build a $1 billion data center in Ohio, a decision that will cost 1,000 jobs and $150 million a year to the local economy.

Trump is trying to repeal the CHIPS Act, which makes this even more uncertain. If you really want to promote manufacturing, keeping policies like this is key!

Businesses have stopped providing guidance about the future, as Sam Ro writes.

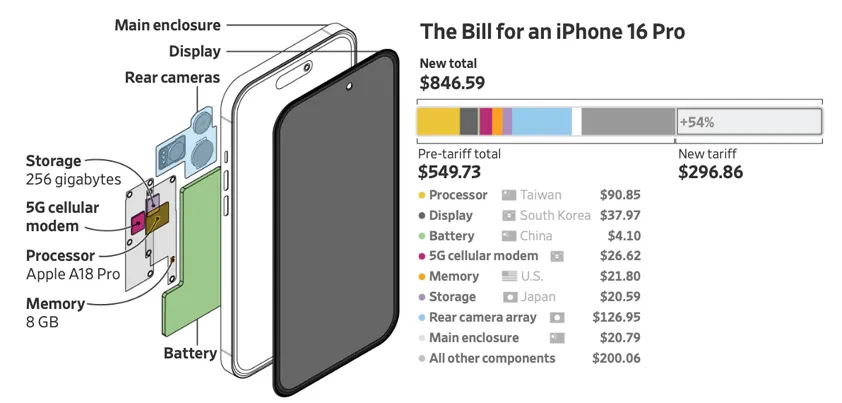

Even if we do move forward with local production—like Trump thinks the US could make the iPhone 4—it will be very expensive. The Wall Street Journal has a great article that goes into detail about what it would take to make an iPhone under tariffs. In addition to the enormous effort and cost required to move production to the US, the resulting phone will be extremely expensive.

In discussions about manufacturing, there is often too much focus on the production of goods and too little attention paid to what the United States really excels at: financialization. As Matt Levine writes:

Currently, many foreign countries sell goods to the United States, and after receiving dollars, they use part of it to buy American goods and the rest to buy American financial assets. Under Trump's system, these countries will have to use all their dollars to buy American goods instead of financial assets.

This means that other countries will no longer be able to buy US stocks and bonds, but will have to find ways to buy goods made in the US. These goods will need to be cheap enough for developing countries to afford, which will:

Forcing the United States to drastically reduce its living standards in order to produce goods cheap enough to export.

It is true that the United States runs a deficit in goods trade, but a surplus in services trade—finance, software, media, and other areas where we excel. If the rest of the world develops parallel entertainment, payment systems, or capital markets, we will lose this intangible advantage.

Additionally, people completely ignore the fact that the United States cannot produce chocolate, bananas, or other raw materials. Some people may say, "It doesn't matter, I don't eat bananas," but this view is too narrow and ignores how the global economy works. For example, although YouTuber Mr. Beast produces chocolate in the United States, the raw cocoa must still be imported from abroad because the United States does not produce cocoa. Similarly, while you may not need to eat bananas, what about the small businesses (or even large creators) that rely on these raw materials?

Take coffee. I had two cups of coffee this morning while editing this post. The beans come from Colombia. The United States can't grow these beans because the climate isn't right. So we have a trade deficit on coffee, but that's not a bad thing. Colombia has a comparative advantage in coffee production, and we buy their coffee because Americans love coffee, and they use their dollars to buy other goods. Both sides benefit.

The frustrating thing is that we shouldn’t dream of making socks in the United States. America’s real focus should be on advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, chips, and biotechnology. If we decouple from or punish foreign partners, it may accelerate their efforts to build their own R&D ecosystems. If they succeed, they will reduce their dependence on these key technologies in the United States. By then, we will lose not only shoe factories, but the next wave of innovation. This is a deeper and more serious consequence.

Potential policy next steps:

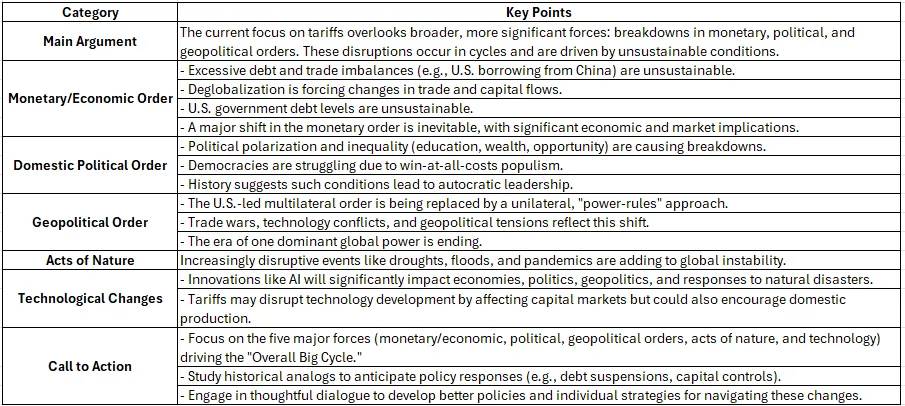

Ray Dalio once said, “Look, this isn’t about tariffs, this is about debt, and we’re going to have to rebalance eventually.” There is some truth to that. He pointed out that we are in a turbulent world and we need to find a way out.

Ray Dalio is right. We are talking about an ecosystem of trust that took decades to build. Until recently, the world was willing to pour money into U.S. Treasuries and let the U.S. dominate many things because they believed that the U.S. would be a relatively stable hegemon.

But if we continue to vent our emotions in unpredictable ways or treat alliances as subscription fees, this intangible trust will gradually disappear, along with the benefits we have gained from it - such as low borrowing costs, supply chain stability, and a dominant seat at every negotiation. The "Overall Big Cycle" that Dalio talks about has arrived, but solving the problem by triggering a global recession and weakening industries is obviously not the best solution.

Even if the White House announces next month, “Oh, forget it, no more tariffs!” the rest of the world has seen the risk that the U.S. might take similar action again. That alone is enough to prompt them to make alternative plans—like strengthening trade ties with each other or finding an alternative reserve currency.

How should the United States respond?

Targeting genuine trade abuses:

Focus on verifiable cases of intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, or unfair subsidies. Rather than imposing blanket tariffs on entire industries, create precise exemptions (for example, for shrimp farmers) or impose punitive tariffs only on proven violations, thereby reducing collateral damage to American companies.

Investing in Workforce and Technology:

Restore the CHIPS Act! High-tech manufacturing incentives could encourage building fabs in the U.S. without punishing consumers with across-the-board tariffs. Fund job training, apprenticeship programs, and community college programs.

Developing a Smart Industrial Policy:

Modernize roads, ports, and broadband facilities to reduce supply chain friction and boost domestic competitiveness. Rather than relying on tariffs, use incentives to attract high-value industries, especially those critical to national security.

Revitalize the Trade Federation:

Improve the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) or rejoin an improved version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) while protecting domestic interests.

Global Leadership:

Demonstrate policy consistency, stop speaking out on social media, and show commitment to fulfilling the terms of the negotiations.

I hope so. But what happens next? We can imagine several scenarios.

Slow fragmentation : Rather than a single dramatic collapse, a trade war would lead to a gradual reorganization of the global system. Over time, the United States would become one of many important players, rather than the world’s center of gravity.

Partial backing off: The government, realizing a recession was imminent, quietly rolled back some tariffs. Markets calmed down a bit, but the damage was done and trust remains low.

Comprehensive crisis and reconstruction: A breakdown somewhere—like a massive sell-off of U.S. Treasuries or a collapse of supply chains—forces all parties to return to the negotiating table to work out a new Bretton Woods. The U.S. may have to give up some privileges to restore stability.

In either case, there will be no complete return to the previous “normal.” Once the illusion of reliability or hegemony is shattered, it cannot be simply re-established. We may be able to salvage a new equilibrium, but it will be on entirely new terms.

Meanwhile, nearshoring may bypass the United States, allies may remain indifferent to our threats, and the “automation plus tariffs” strategy may ultimately fail to create many manufacturing jobs.

These tariff wars and bond market panics are more than short-term news; they could reshape how capital flows, supply chains are formed, and how the world cooperates on issues ranging from financial crises to wars. Rather than a single catastrophic moment, we may see a series of smaller collapses that culminate in a world where the United States is no longer central and other countries have re-formed themselves.

Once we destroy this invisible fabric of trust, partial concessions cannot be repaired. If we fail to recognize this early, we may get lost in a series of small crises and temporary alliances, only to discover, ironically, that the old system, despite its flaws, was the best deal the United States could have.

What can you do?

The following content is not investment advice and is for reference only.

Check your portfolio:

Make sure you know how much of your portfolio is made up of stocks, bonds, and other assets. Consider diversifying overseas. Understand the exact makeup of the ETFs or mutual funds you own. Holding a mix of stocks, cash, bonds with different maturities, and even other assets like real estate can help balance risk.

Build cash reserves:

If the market is volatile, having a few months' worth of living expenses in cash (or assets close to cash) is a good buffer to avoid being forced to sell investments at an inopportune time.

High Yield Savings Account (HYSA):

If you have a lower risk appetite, you can put your money in a high-yield savings account. This type of account not only generates income but also allows quick access when needed. I personally keep about half of my portfolio in this type of account.

Avoid panic selling:

News headlines can be scary, but panic selling is generally unhelpful. If you own a diversified, long-term portfolio, short-term market fluctuations are often just "noise."

If you see worrying news, don't let fear dictate your decisions. This uncertainty isn't going away anytime soon, so stay calm, be clear about your investment time horizon, and adjust your portfolio's risk level to what you're comfortable with. Thank you, everyone!

Discussion on tariffs:

I have discussed tariffs at length in many of my previous newsletters and have interviewed Erica York of the nonpartisan Tax Foundation and Stan Veuger of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) four times. No one likes tariffs!

Impact of foreign investors:

Foreign investors own 18% of the U.S. stock market, which could make market volatility more intense.

Oil prices and bond markets collapsed simultaneously:

The simultaneous collapse of oil and bonds is unprecedented. Russia is clearly not too happy about this.

Complexity of Manufacturing:

Consider the various inputs into the manufacturing process — processors, displays, camera modules, memory, batteries, glass, chips, casings, assembly, etc. It’s a complex process, and building such production capacity here in the United States will take a long time.

Importance of Workforce Issues:

One thing to note about labor is that we do outsource a lot of external costs to other countries, where workers often do very hard work for very low pay. Part of the reason for this is the development ladder - while the work is hard and the pay is low, factory wages can be a better option for emerging economies than the alternative. Problems won’t suddenly become perfect, and blanket tariffs won’t solve that complexity. In fact, tariffs could make the problem worse if thousands lose their factory jobs and fall back into extreme poverty.