Original Author: @desh_saurabh

Original Compilation: TechFlow

Zero-Sum Attention Game

In 2021, each crypto asset had an average of approximately $1.8 million in stablecoin liquidity. However, by March 2025, this figure had plummeted to just $5,500.

This chart visually demonstrates the decline in average values while also reflecting the zero-sum nature of attention in today's crypto landscape. Despite the number of tokens surging to over 40 million assets, stablecoin liquidity (as a rough measure of capital) remains stagnant. The result is brutal—less capital per project, weaker communities, and rapidly declining user engagement.

In such an environment, fleeting attention is no longer a channel for growth but a burden. Without cash flow support, this attention quickly shifts without mercy.

Revenue as the Anchor of Development

Most projects still build communities in the 2021 style: creating a Discord channel, offering airdrop incentives, and hoping users will shout "GM" (Good Morning) long enough to generate interest. But once the airdrop ends, users quickly leave. This is unsurprising, as they have no reason to stay. This is where cash flow becomes crucial—it's not just a financial metric but an important proof of project relevance. A product that generates revenue means there is demand. Demand supports valuation, and valuation, in turn, gives tokens gravity.

Although revenue may not be the ultimate goal for every project, most tokens simply cannot survive long enough to become foundational assets without it.

It's worth noting that some projects are positioned differently from other parts of the industry. Take Ethereum, for example, which doesn't need additional revenue because it already has a mature and sticky ecosystem. Validators' rewards come from approximately 2.8% annual inflation, but the EIP-1559 fee-burning mechanism can offset this inflation. As long as burning and earnings balance, ETH holders can avoid dilution risks.

But for new projects, they don't have such luxurious conditions. When only 20% of tokens are in circulation and you're still struggling to find product-market fit, you're essentially like a startup. You need to be profitable and prove your ability to sustain profitability to survive.

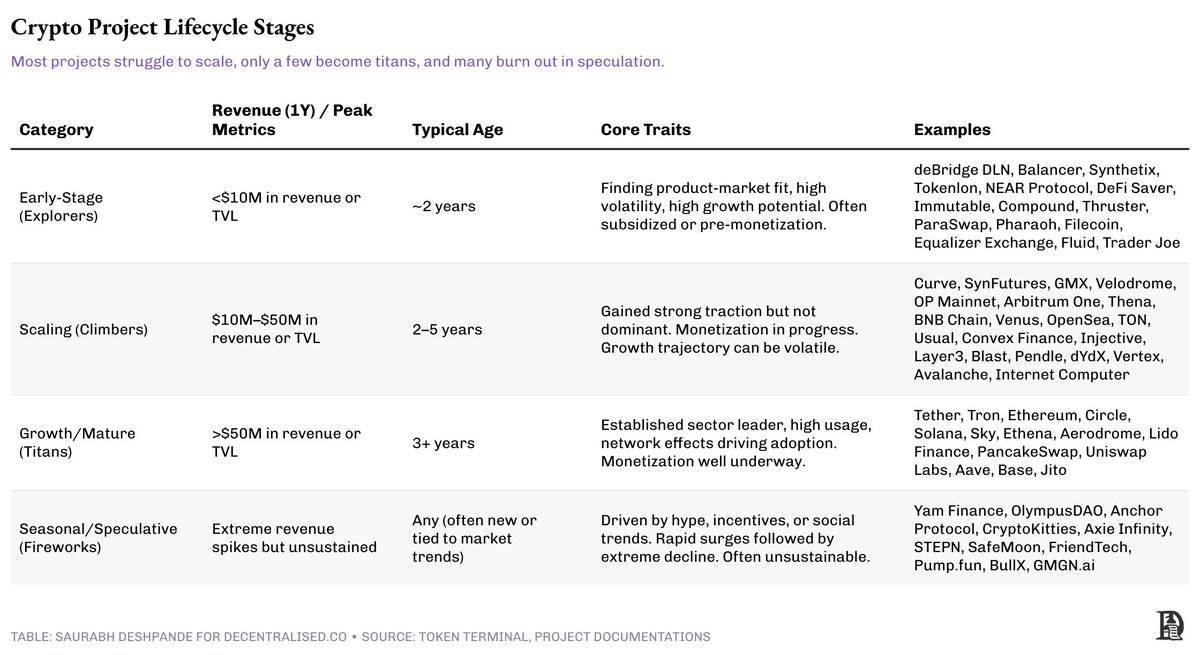

Protocol Lifecycle: From Explorers to Giants

Similar to traditional companies, crypto projects are at different stages of maturity. At each stage, the relationship between projects and revenue—and whether to reinvest or distribute income—changes significantly.

Explorers: Prioritizing Survival

These are early-stage projects, typically with centralized governance, fragile ecosystems, and more focused on experimentation than monetization. Even if they have revenue, it's often volatile and unsustainable, more reflecting market speculation than user loyalty. Many projects rely on incentives, grants, or venture capital to sustain themselves.

For example, projects like Synthetix and Balancer have existed for about 5 years. Their weekly revenues range between $100,000 and $1 million, with some exceptional spikes during peak activity. Such dramatic fluctuations and pullbacks are typical of this stage, not signs of failure, but manifestations of volatility. The key is whether these teams can transform experiments into reliable use cases.

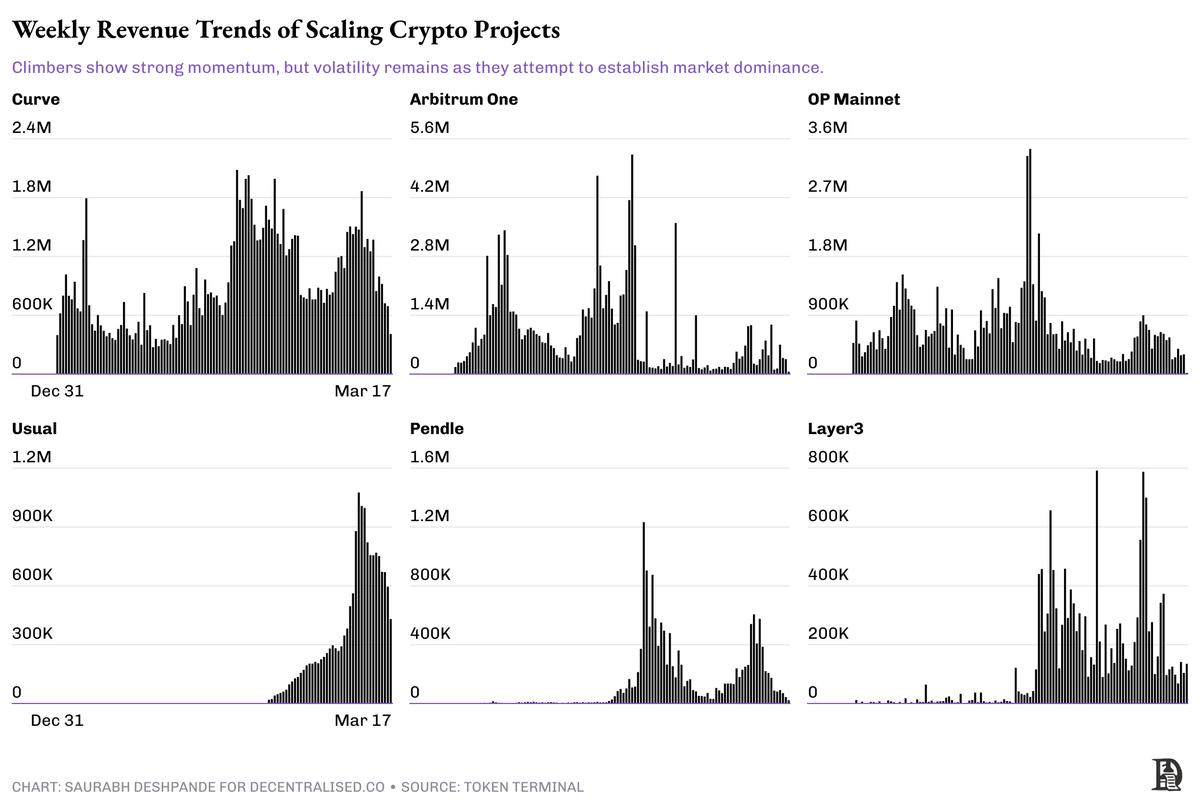

Climbers: Gaining Traction but Still Unstable

Climbers are projects in an advanced stage, with annual revenues between $10 million and $50 million, gradually moving away from token issuance-driven growth. Their governance structures are maturing, shifting focus from pure user acquisition to long-term user retention. Unlike explorers, climbers' revenues can prove demand across different cycles, not just driven by one-time hype. Simultaneously, they are undergoing structural evolution—transitioning from centralized teams to community-driven governance and diversifying revenue sources.

Climbers are unique in their flexibility. They have accumulated enough trust to attempt income distribution—some projects are beginning revenue-sharing or buyback programs. But simultaneously, they face the risk of losing momentum, especially when over-expanding or failing to deepen their moat. Unlike explorers' primary task of survival, climbers must make strategic trade-offs: growth or consolidation? Distribute income or reinvest? Focus on core business or diversify?

The vulnerability at this stage isn't in volatility but in stakes becoming real and visible.

These projects face the most challenging choices: distributing income too early might hinder growth, but waiting too long might cause token holders to lose interest.

Giants: Ready to Distribute

Projects like Aave, Uniswap, and Hyperliquid have crossed the threshold. They can generate stable revenue, have decentralized governance, and benefit from strong network effects. These projects no longer depend on inflationary token economics and have a solid user base and market-validated business models.

These giants typically don't try to "do it all". Aave focuses on lending markets, Uniswap dominates spot trading, and Hyperliquid is building a DeFi stack centered on execution. Their strength comes from defensible market positioning and operational discipline.

Most giants are leaders in their respective domains. Their efforts are usually concentrated on "expanding the pie"—driving overall market growth rather than simply expanding their market share.

These projects are the type that can easily conduct buybacks and still maintain operations for years. While not completely immune to volatility, they have enough resilience to withstand market uncertainties.

Seasonal Players: Noisy but Lacking Foundation

Seasonal players are the most eye-catching yet most fragile type. Their revenues might rival or even exceed giants in a short time, but these revenues are primarily driven by hype, speculation, or brief social trends.

Projects like FriendTech and PumpFun can create massive engagement and trading volumes in a short time but rarely convert these into long-term user retention or sustainable business growth.

These projects aren't inherently bad. Some might adjust direction and evolve, but most are short-term games riding market momentum rather than building enduring infrastructure.

Lessons Drawn from Public Markets

Public stock markets provide beneficial analogies. Young companies typically reinvest free cash flow to scale, while mature companies distribute profits through dividends or stock buybacks.

The following chart shows how companies distribute profits. As companies grow, the number of companies paying dividends and conducting buybacks increases.

Crypto projects can learn from this. Giants should distribute profits, while explorers should focus on retention and compound growth. But not every project is clear about which stage they belong to.

Industry characteristics are equally important. Utility-like projects (such as stablecoins) are more like consumer staples: stable and suitable for dividends. This is because these companies have existed for a long time, and demand patterns are largely predictable. Companies rarely deviate from forward-looking guidance or trends. Predictability allows them to continuously share profits with shareholders.

Here's the translation:High-growth DeFi projects are more like tech industries - the best value allocation method is a flexible buyback plan. Tech companies typically have higher seasonal volatility. In most cases, their demand is not as predictable as some more traditional industries. This makes buybacks the preferred way to share value.

If a quarter or year performs exceptionally well? Pass the value out through share buybacks.

Comparison of Dividends and Buybacks

Dividends have stickiness. Once a dividend is promised, the market expects consistency. In contrast, buybacks are more flexible, allowing teams to adjust the timing of value distribution based on market cycles or token undervaluation. From about 20% profit allocation in the 1990s to about 60% in 2024, buybacks have grown rapidly in recent decades. In terms of dollar amount, buybacks have exceeded dividends since 1999.

However, buybacks also have some drawbacks. If communication is poor or pricing is unreasonable, buybacks may transfer value from long-term holders to short-term traders. Additionally, governance mechanisms need to be very tight, as management typically has key performance indicators (KPIs) such as improving earnings per share (EPS). When a company buys back shares in circulation (i.e., outstanding shares) with profits, it reduces the denominator, artificially inflating EPS data.

Dividends and buybacks each have their applicable scenarios. However, without good governance, buybacks may quietly benefit insiders while the community suffers.

Three key elements of a good buyback:

Strong asset reserves

Well-considered valuation logic

Transparent reporting mechanism

If a project lacks these conditions, it may still need to be in the reinvestment phase rather than conducting buybacks or dividends.

Current Income Distribution Practices of Leading Projects

@JupiterExchange clearly stated at token launch: no direct income sharing. After 10x user growth and having sufficient funds to sustain operations for years, they launched the "Litterbox Trust" - a non-custodial buyback mechanism currently holding about $9.7 million in JUP tokens.

@Aave has over $95 million in asset reserves and distributes $1 million weekly for buybacks through a structured plan called "Buy and Distribute", launched after months of community dialogue.

@HyperliquidX goes further, using 54% of its income for buybacks and 46% to incentivize liquidity providers (LPs). To date, it has bought back over $250 million in HYPE tokens, fully supported by non-venture capital funds.

What do these projects have in common? They only implement buyback plans after ensuring a solid financial foundation.

The Missing Link: Investor Relations (IR)

The crypto industry loves to talk about transparency, but most projects only disclose data when it serves their narrative.

Investor Relations (IR) should become core infrastructure. Projects need to share not just revenue, but also expenses, runway, asset reserve strategies, and buyback execution. Only then can confidence in long-term development be built.

The goal here is not to claim that one value allocation method is the only correct one, but to acknowledge that the allocation method should match the project's maturity. In the crypto realm, truly mature projects are still rare.

Most projects are still finding their footing. But those that get it right - projects with revenue, strategy, and trust - have a chance to become the "cathedrals" (long-term, robust benchmarks) that this industry desperately needs.

Strong investor relations are a moat. They can build trust, mitigate panic during market downturns, and maintain ongoing institutional capital participation.

Ideal IR practices might include:

Quarterly revenue and expense reports

Real-time asset reserve dashboard

Public record of buyback execution

Clear token distribution and unlock plan

On-chain verification of grants, salaries, and operational expenses

If we want tokens to be viewed as genuine assets, they need to start communicating like real businesses.